THE BEFORE YEARS – PART I

Some say ’63, ’64 or even ’65. Others think ’68. For me, it was ’67, the end of adolescence. Commencement was over and we had said our goodbyes. Yearbooks sported both the sincere and the trite, those embarrassing scribbles scanned but not read. Back home, we searched the pages, reading and re-reading the notes left behind. Many a familiar face had been seen for the last time. Some would actually be missed. The lockers, the building quads, the cafeteria, the student parking lot, had all been eerily abandoned. Still, the buildings were not the only things locked and empty. Each of us was dealing with our own pending aloneness, the finality of the whole thing. We were now officially “Old enough to kill but not for votin.” It was a time for treading into the unknown and it had as much to do with the world around us than forced adulthood. The edge of the conveyor belt was right there. We were falling into an unavoidable abyss filled with uncertainty. We were entering a dangerous world filled with notions of violence that had been drilled into us since elementary school. After all, we knew all about mushroom clouds. We were the “Duck and Cover Kids,” the newly anointed draft card carrying constituents that grew under the shadow of now silent air raid towers. Our youthful naiveté, long since influenced by our societies cognitive biases, was coming to an end; more abruptly for some than others.

At least for now, it was the beginning of the “Summer of Love.” Before the end of the month, I was going solo, driving the coast up to Monterey. It was my first real experiment with independence. Responsibility could wait. I was off to see Jimi, Janice, and Gracie. Unbeknownst to the unaffected, it was also the beginning of the “Long-Hot-Summer.” Across the nation, that season marked 150 race riots; 85 people wound up losing their lives. Six months earlier, we had experienced another loss. Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffe died on a Cape Kennedy launch pad. In fact, the space program was not infallible.

Just five years earlier, we were still standing in line for our four shots. At least we could skip the polio needle, it was replaced by Sabin’s sugar cube. Meanwhile, Rachel had penned her “Silent Spring” while Glenn completed his three laps outside the atmosphere. Cracker Jack boxes in hand, we were glued to the TV. When it was over, we peddled on over to the plunge, or was it the sandlot? Given the affluence level of the neighborhood, our one car households required alternate modes of transportation. That was provided courtesy of J. C. Higgins, Huffy, or Schwinn. Regardless, these two wheeled extensions of ourselves soon became cobwebbed covered memories, permanently mothballed victims of a pending pubescence. That September, it was off to the big dance, high school. Even if it meant walking, no self respecting first year prep would be caught dead riding a bike. That was for children. Even our once coveted P. F. Flyers and Red Ball Jets were being replaced by Jack Purcell’s, Wallabies and Chuck-a-Boots. Like it or not we were now officially “Freshmen,” invisible to the upper castes yet in a place where every blemish, every foible never went unnoticed. Little did we know that our visceral insecurities was a shared experience. Our classmates and the nation itself was right there with us. As new roles were being assigned, societal morays begrudgingly moved left and right. The pace of change questioned the unquestionable. It was becoming clear, being white didn’t automatically make us, well, right.

Backlit by a decade old defeat and a never ending cold war, the country was still living in the aftermath of McCarthyism, the Bay of Pigs, and the remnants of what was called a “Police Action.” We were just old enough to get some sense of this with the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. For our parents, this was a recurring reminder, a continuing nightmare. War was never more than a heartbeat away. America, the leader of the free world, was duty bound to thwart the “Red Menace.” After all, Nikita said he was going to bury us. To a bunch of soon to be ninth graders, the ensuing blockade off the east coast brought a sense of foreboding tangibility to what had been nothing more than a string of ancient B&W newsreels. Pics taken from a US U-2 spy plane revealed something different; Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles were installed just 90 miles off of Florida. Even us kids knew that was too close. Fortunately, the saber rattling ended. The east/west tap dance returned to a safer distance, West Berlin and Checkpoint Charlie. Still, we were scared. Annual military conscriptions grew from 82,000 to 119,000. Below our radars, the happenings in southeast Asia had gone mostly unnoticed; US troop levels in Vietnam now stood at 16,300, some 5,000 more than the previous year. As we were soon to find out, “We Ain’t Seen Nothin Yet.”

There were unsettling tidbits coming from within. Oblivious to the continuing practice of intended segregation in California, we would come to know Watts Willowbrook. It was just about the same time MLK was penning his “Letter From [the] Birmingham Jail.” In the distant South, white supremacists would blow up the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four young African American girls, one 11 and three 14. Kennedy would momentarily turn his attention away from protecting the free world and focus on our own domestic unrest. He would give his most direct speech to the American people in his “Report on Civil Rights.”

The declaration had been made: Equality for all Americans was a moral issue, a message that came too late for one of the founders of the civil rights movement, Medgar Evers. He had been murdered. As the year continued to unfold, MLK would take center stage during the March on Washington. This time, in front of a crowd of 250,000, he would make it clear, he had a dream.

Twice a day, we would get these flashes, these bits and pieces of a world outside of our sheltered peripheral vision. First, it was from the front page of the morning paper. That had my fathers attention. He knew how to master its folding as he maneuvered around his over-hard eggs, toast, and coffee. It was usually a silent affair. Sometime around 6:00 p.m., dad’s sporadic return voyage would stop at the dinner table with its unobstructed view of the television. There we got the second flash. Since he was mostly an NBC man, he invited the newly colorized images of Huntley and Brinkley in every night. The black and white versions of Cronkite and Howard K. would accept similar invitations in the living rooms down the street. Still at this age, meals required mandatory attendance. For 30 minutes in the morning and 30 minutes in the evening, this is where current affairs were catalogued, sometimes even discussed. All of this was but a prelude. For it was now 1963 and it wasn’t over. It was the beginning of fourth period, just two months into being high-schoolers, when we got the news: The president had been shot and seriously wounded. Within the hour, our teacher would quote Walter:

“From Dallas Texas—The flash apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1:00 p.m. central standard time, two o’clock eastern standard time, some 38 minutes ago”

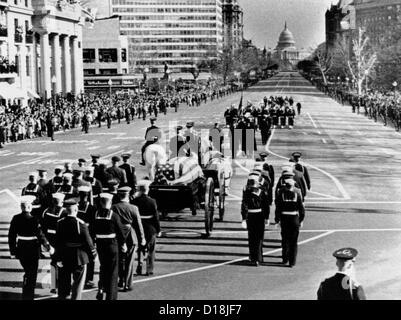

How could this happen? This can’t be real. JFK had captured our attention, our very imagination. He was young and didn’t look like our grandfathers. We could relate. He spoke directly to us, the legion of impressionable fledglings. Our possibilities were just coming into focus. It was a full dose of reality. Hopes and dreams were permanently dampened. A procession, a drum beating cadence, Chopin’s Funeral March, and John John’s salute were indelibly etched in our minds. A caisson from another era carried a flag draped casket. Sporting stirrups with boots in reverse, a restless, riderless horse, a half-Morgan named Blackjack, followed close behind. At the end of the day, a flame would be lit, it would be eternal. Innocence once removed, this was our baptismal into adolescence, another uncomfortable glimpse of the world around us. This was a reality we weren’t ready for. After all, we had just barely found homeroom. Perceptions and gross generalizations being what they are, both “Tweens” and adults would be left with their own versions of what was. Some of us pined for summers past. Some just wondered “What’s Next?” Just another dose of reality that’s what’s next, as we witnessed Jack Ruby shoot and kill Lee Harvey. This was all just too much. Unavoidable adulthood was now just four years away. That was a lifetime. It’ll be safe by then, won’t it?

It was now 1964. Berkeley’s Jack Weinberg warned us: “Never trust anyone over 30” while Dylan and Cook sang about change. Bob would make clear that the “Order is Rapidly Fading” while Sam lamented how his “Brother Kept Knocking Him Back Down on His Knees.” Us juveniles needed to pay attention. Casual listening focused on puppy love was just a respite from songs carrying some heavy shit. Yet, timing being what it is, avoidance was easy. We were distracted. There was an invasion going on and it was British. Our short attention spans were busy sorting out the “Mods” from the “Rockers.”

The Beatles, the Stones, the Animals and the Dave Clark Five led a wave of new sounds, some with the familiar tinge of black retro-blues. The Yardbirds, the Kinks, the Hollies and a host of one and two hit wonders would also cross the pond. The competing vibrations from LA, San Francisco, Detroit, Philly, Boston and the Village would continue to flood the airways. Duane Eddy, Dick and his Del Tones, the Champs, the Tornados, the Sufaris, and even the Ventures, were already memories; walking, not running, to the door. Stereo was in, Mono was out. It was a time when tennis shoes gave way to “Beatle Boots.” It was all about the music, cars, short-skirts, and tight sweaters, hormones notwithstanding. From here on out, it was going to be “A Hard Days Night.”

That same year, Dr. Strangelove taught us how to stop worrying and love the bomb. After all, in spite of “Fail Safe” and “Seven Days in May” we had long since quit counting how many atolls had disappeared under a nuclear cloud. “Goldfinger” was 007’s latest foe, “Mary Poppins” was handing out spoons full of sugar while a spaghetti eating Clint held a Fistful of Dollars. When we were busy getting “Bewitched” or “Dreaming of Jeannie,” the Minnow had been lost. Lucky us–NBC’s peacock let us roam around a colorized Ponderosa. Still, Sunday night was reserved for Ed Sullivan. He just might be showcasing the latest and greatest from the UK.

And then there were sports. Final—the Cardinals beat the Yanks, the Celtics upped the Warriors, the Browns blanked the Colts, the MapleLeafs took the Red Wings, an Olympian named Hayes won the 100, and Cassius, soon to be Muhammad, knocked out Sonny. It was the same year my Dad’s favorite driver, Eddie Sachs died at the 500. We listened to it on the radio.

All in all the world kept spinning. On the heels of the Monson Motor Lodge Protests, and a 60 day filibuster by southern Dixiecrats, came the passage of the Civil Rights Act. President Johnson had carried forward the vision outlined by JFK just a year and some change earlier. With the legislative ink barely dry, violence would only rear its ugly head in Harlem, Rochester, Jersey City, Philadelphia and of all places, Dixmoor Illinois. Another teenager, this time fifteen year old James Powell, would be shot three times by an off duty New York City police officer. It was a pattern, continuously repeated. For an obtuse suburban dwelling white America, this was something distant, out of sight, out of mind, and not in my neighborhood. For us, these were incidences affecting the black inner city poor and a blatantly segregationist south. Besides that other thing was still brewing. In just two years, troop levels in Vietnam had more than doubled now standing at 23,300. Annual inductions hovered around 112,000. The Free Speech Movement and the burning of draft cards had begun. In the Soviet Union, Khrushchev was out, Brezhnev was in. The US nuclear stock pile had exceeded 31,000 warheads. The Soviets had more. ICBMs, ABMs, MIRVs, take your pick.

In other news, cigarettes cause cancer. Anchorage was hit by the biggest earthquake on record. We didn’t know that TV watching and all those commercials had taken their toll: we were emerging members of the nation’s consumer republic. Someday we would all have our own BankAmericard; At least us boys anyway.

You must be logged in to post a comment.